Ayden Grout: Psychogeography and the New Lenses of Landscape at Flux Factory

by Liz Janoff

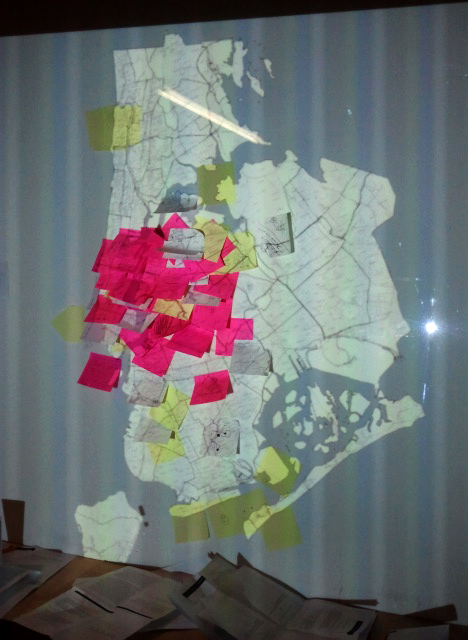

“Draw or describe one thing you saw on the way to Flux Factory. Place your Post-it on the map in the place that you saw this thing” (Directions to the audience for Flux Factory’s evening of psychogeography)

After arriving at Flux Factory for their March salon, I was instructed to draw ‘how I got to Flux Factory,’ on a Post-it note, later placed on a large projected map of New York City at the point of my departure––my apartment. Inspired by, as organizer of the event Ayden Grout describes, “the ways we laminate our individual environment with memory,” the salon included several other audience mapping activities as well as five artist presentations on the theme and title of the event, Psychogeography and the New Lenses of Landscape.

The topic engaged Grout’s own fascinations as a Flux artist-in-residence as well as her background working for the participatory art group Odyssey Works, who specialize in performances for small audiences. In a wide range of subjects and media––from landscape photography and ocean-inspired music to astrology––the curated discussions sought to draw relationships between recent evolutions in the landscape genre and artist-initiated projects linked to ‘psychogeography,’ or creative forms of mapping.

As described for the audience, the term psychogeography, coined by co-founder of the Situationalist International, Guy Debord in 1958, refers to any personal or ‘inventive’ strategy of exploring cities. In Debord’s words, it involves examining the “specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.” Associated practices include drifts, or aimless wanderings through cities, meant to heighten psychological encounters. In this spirit, each of the artists in the salon presented his or her own drift, or method of engaging with urban landscapes, whether through art, music, or less conventional activities (particularly the ‘astrological walking tours’ discussed by astrologer Bess Mastassa, for example.)

Further reading material on psychogeography was distributed in the program pamphlet at the salon, referencing the ‘intoxication’ artists and philosophers have had historically with wandering in cities; however the salon’s presentations were more cynical and often humorous. They seemed instead to play with, or pervert, the excessive re-mapping, documenting, and touring of today’s landscapes in cities or elsewhere. Two presentations in particular––a performance by duo N.D. Austen and Ida Bendetto, and a talk by photographer Lizzie Eisenstein––achieved this by drawing attention to today’s urban forms, entertaining sites of urban decay or in Eisenstein’s case, hours spent on the virtual platform, Google Earth.

The talk given by Eisenstein seemed most relevant to Grout’s theme, confronting recent, virtual configurations of landscape as a means to rethink her practice in traditional landscape photography. She presented on what she called the “passive” act of collecting Google Earth images similar in aesthetic to her analog photographs. Though this work is still in its initial stages, the process, she explained, has helped her reckon with the sense of authorship she generally feels in taking landscape photos. Her insights into the flaws and make-up of the database displayed the most evident ‘psychogeographic’ play though, along with the results of her detailed database searches. This included several types of places, “family restaurants across America” for example, in combination with chosen light or weather conditions.

While Eisenstein spoke directly to the theme, the act performed by N.D. Austen and Ida Bendetto of Wanderlust––known for their pop-up performances––seemed out of place at first. They began by engaging the audience in a couples’ argument on ‘what’ they should perform. Although not much context to their act was provided, the improvised skit was assumed to be an adaptation from their project, Wanderlust’s Illicit Couple’s Retreat, which involves immersive audience tours to an abandoned honeymoon resort located in Pennsylvania. One of the more established presenters, the Wanderlust duo refers to this sort of work, according to the Daily Beast as “transgressive place-making,” tailoring their immersive experiences to “preferably history-rich locations”––an approach particular to many of today's performance works.

Though I was at first unsure about Wanderlust's role in the event, the performance brought out the threads of participatory engagement found throughout the evening’s program and in line with Grout’s arts background. After the showcase of the five starkly different projects––the gaps between them alleviated by the playful salon-style of the event––members of the Flux audience were finally able to drink and converse about the presentations over their own map drawings at the night’s close. Read more about the salon artists and their presentations on the event’s Facebook page.

Why did you decide to organize this month's salon on the theme of "psychogeography" and landscape?

AYDEN GROUT: In many ways, landscape is taking on some of the qualities of portraiture in contemporary art. Walking and mapping are particularly salient tropes, so inviting Bess to talk about how movement through the city is tied to our astrological selves seemed fitting. She's giving us a new lens for the city. Then there are people like Wanderlust that are becoming our guides to other layers of the urban landscape and giving us passports into territory we are often barred from. It's a fascinating trajectory to watch, especially because it often requires new levels of participation for the audience of a work.

How does this theme intersect with your current art practice?

GROUT: My current practice examines the interstices between public and private space, for example how a hotel is an interior that purports to have privacy while still being semi-public. There is a sense of emptiness to the furniture, which is usually laden with memory. But hotels aside, I think that many artists are finding ways to take landscape and imbue geography with the intimacy of private space. In my work with Odyssey Works too, there is so much consideration of the interstices of personal experience with public space. Knowing our individual, our sole audience member, requires knowing the places that he or she finds remarkable, whether positive or negative.