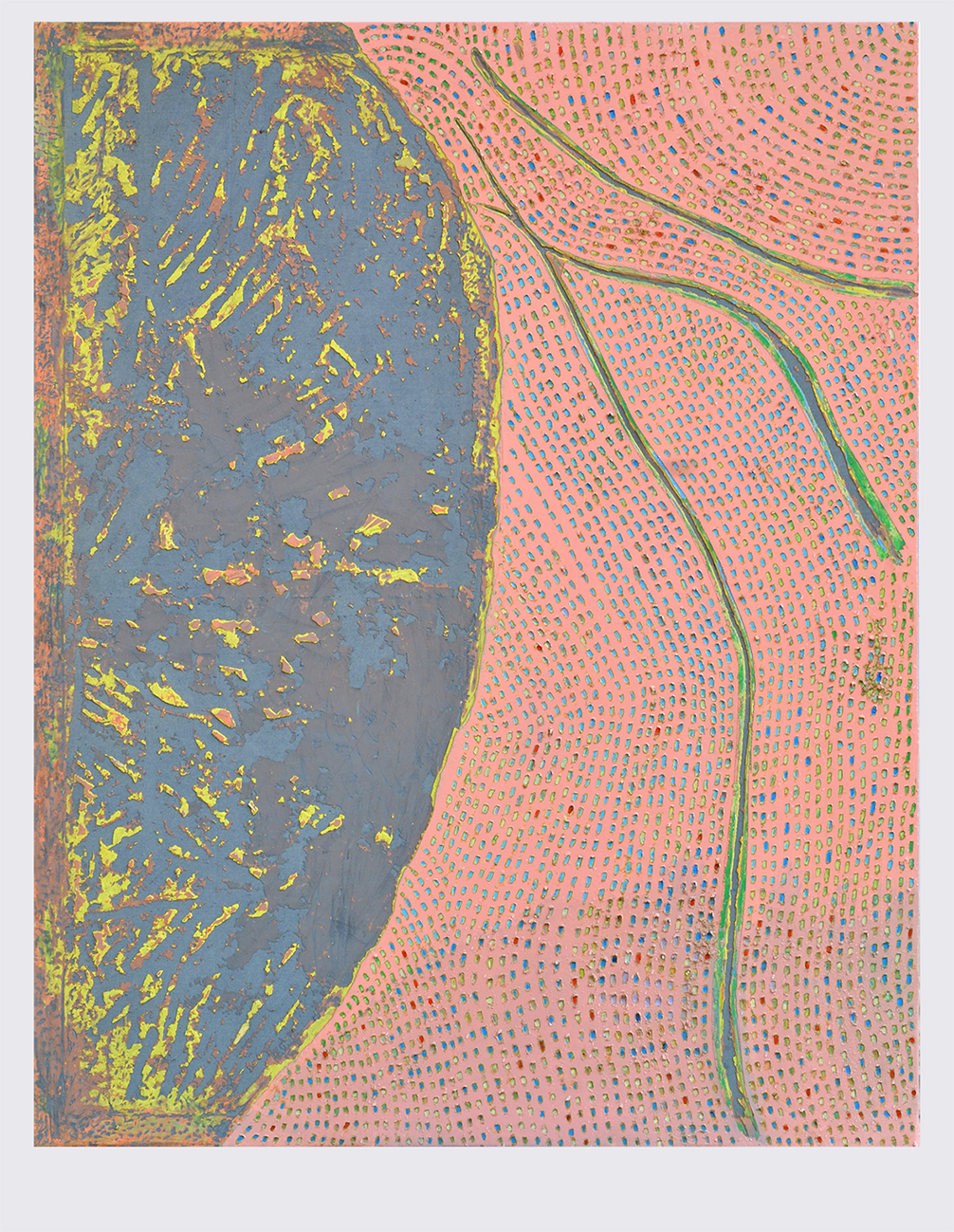

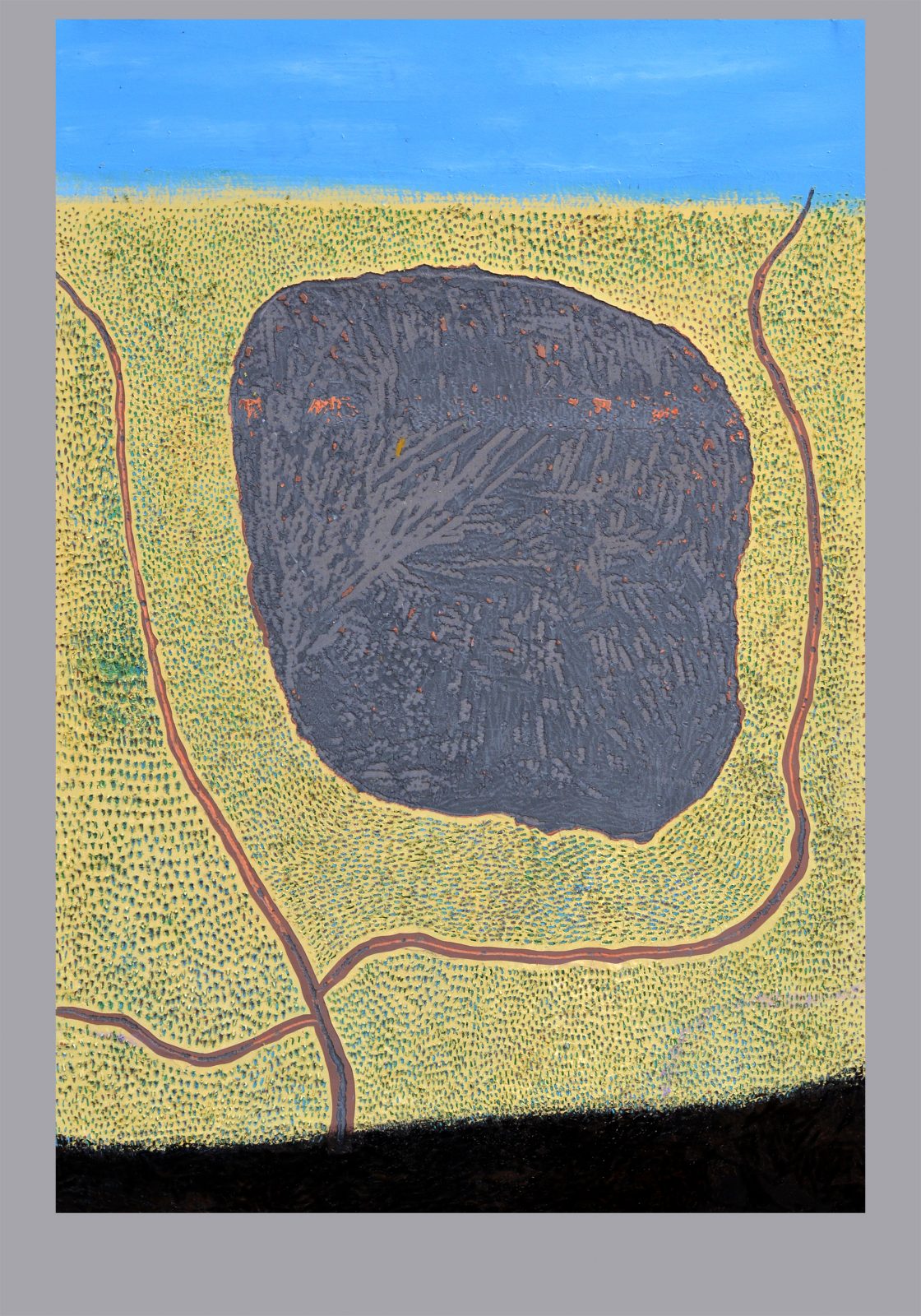

Throngkiuba Yim | Nagaland, India

Kolkata based artist Throngkiuba Yim, who grew up in Dimapur, Nagaland, the far Eastern state of India, is here in conversation with Paola Loomis, EAS contributor.

First I want to thank you for the consistency in your art. It goes right to the point and presents itself as a concrete document which we directly engage. In your work the dichotomy of nature versus culture is rethought artistically, finding occasion for dialogue and exchange. This is the way your project speaks to the viewer. Hence some questions:

When and why did you begin to focus artistically on the environment ?

The focus of my work started to shift to environmental issues after I moved from Kolkata to Santiniketan, which is approximately three hours away, to pursue a Master in Art at the Visva Bharati University. It was then that I started meditating on how our climate is being thrown out of balance with the increase of the human population and the extraction of resources, resulting in what feels like looming devastation. I wish to share my sense of urgency with the community, coupled with my nostalgia for my childhood days of trees and fields I wish to see again, where I played games and hung around in the wilderness. I began to feel a sense of vulnerability, both for myself and for this planet, as I watched the city expand around me, as I witnessed the lack of waste management, the pollution and the incredible amount of traffic. I wish to explore ways in which art can contribute to instill positive changes, or at the very least, to provide a sense of solace to our society.

It sounds like your childhood was deeply rooted in nature. How did your love of nature connect with your art school studies and your practice as an artist?

During my college years in Kolkata, from 2011-2015, I was subconsciously aware of the city’s expansion, rapid increase in population, noise and pollution. I noticed to a certain extent even in my home city the threat to the ecological balance due to increase of automobiles and population. But I started to focus more on this threat only after moving to Santiniketan.

The first thing that inspired me was the contrast between Kolkata and Santiniketan, contrast that introduced me to seeing both art and space from multiple perspectives. The second thing that moved me to create art around the concept of the environment, were the memories of my childhood years, at the fresh green meadows where I played games.

Are these memories of your native places? Can you tell us more about Nagaland? And when did you move from Nagaland to Kolkata?

Dimapur is the town where I grew up until I moved to Kolkata in 2011, right after 12th grade. However my native place is in Tuensang district, and that is my ancestral place. Nagaland is located at the Northeastern border of India.

The Naga territory existed with ‘full sovereignty’ before the advent of the British colonial expansionism in 1881. In 1947 the people of India and the Naga territory were liberated from the British rule. Naga had informed the British government that they would not join the Union of India, but after India regained sovereignty from British rule, India included Nagaland in its territory. Since the 1950s, and until today, the state has experienced insurgency as well as inter-ethnic conflict.

The state is inhabited by 16 major tribes. Each tribe is unique in character, language and art. Weaving is a traditional art handed down through generations. Each tribe has unique designs and colors, producing shawls, shoulder bags, decorative spears, table mats, wood carvings, and bamboo works. Among many tribes the design of the shawl denotes the social status of the wearer. Folk songs and dances are also essential ingredients as well as expressions of the traditional Naga culture. The tribal dances, for example, can give an insight into the inborn Naga people’s reticence. Unfortunately very few are kept alive.

That is very interesting. Is your art rooted in this “inborn reticence” of the Naga people?

The inborn reticence of the Naga people carries both advantages and disadvantages, politically and socially, and it is a very complex feature. Yes, my artistic work is conceptually very much rooted in this “inborn reticence”, but it is not in regard to the visual choices. The majority of contemporary Naga artists practice art in very traditional ways, both visually and in the mediums they use. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that Naga traditional textile is very much abstract.

Looking back to your studies in art school, which were the most significant for you?

Every stage of my art studies was very important, from developing my practice and concepts, and growing as an artist, to getting to know myself better and understanding life.

I appreciate your answer because you put the focus more on yourself as a protagonist of your studies, than on the studies and art school programs themselves. In any case, I suppose that there are artists, thinkers and poets who have been important to you.

My all time favourite artists are Jackson Pollock and Willem De Kooning. I am fascinated by and I developed courage from De Kooning’s journey to become an artist, arriving to the USA from the Netherlands as a stowaway hidden in the storeroom of a ship. During the Depression many young artists were employed in the Federal Art Project by the US government, and most of them were immigrants. At that time immigrants had a better chance than today in the USA.

My early style was hugely inspired by Jackson Pollock’s automatism and by Willem De Kooning’s subconscious distortion of figures. Moreover, I was intrigued by their zealous continuous effort and strong relationships at the beginning of the Abstract Expressionist movement. Those artists would meet up almost every day at the Stewart’s Cafeteria in New York and discussed art for hours, something that is really rare these days among young artists. Our world has become too busy and self-centered.. Unfortunately I am part of this.

But you are aware of this, and that makes a difference. It is something that we can feel in your art.

Let’s take “Biggest Misconception” and its texts: what is the role of poetry in your research?

The friends who helped me in bringing “ Biggest Misconception” to life were Lavrenty Repin from South Africa, who wrote the poem following my narration, and William Clark from Philadelphia, who did the sound editing. I was moved by the crisis in Syria. Artists should always be unbiased in their artistic expression, irrespective of religion, caste, political party and race. Instead they should fight for humanity. Religion, caste, tribes, political parties and race are like different boxes in which we blindly fall, they are never the answers for peace.

('Biggest Misconceptions', inspired by the events in Syria. Toys on Wood, Fiberglass, Enamel Paint, Video)

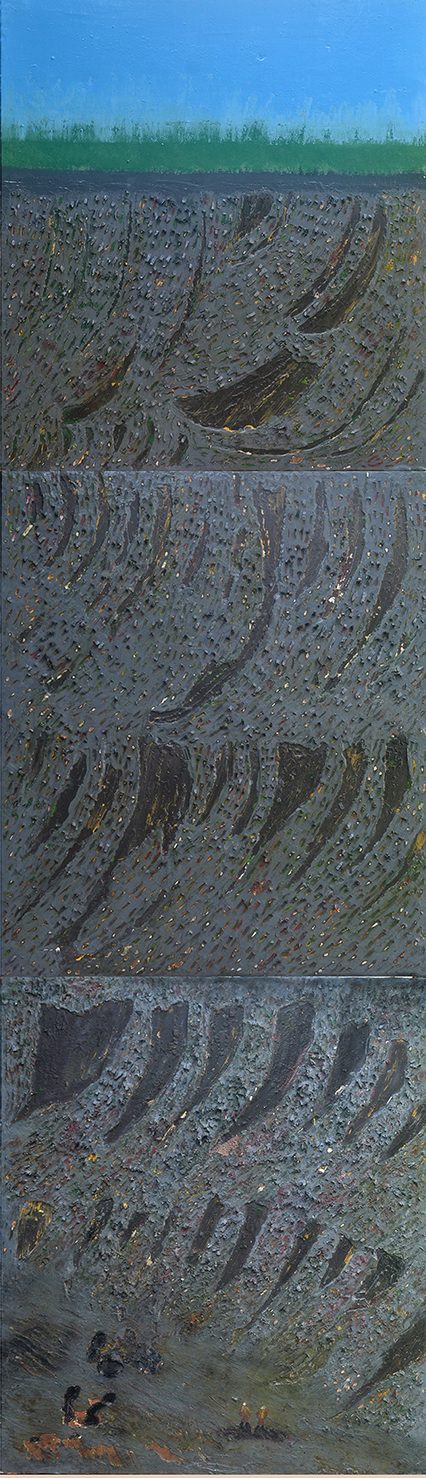

Some materials or techniques push you to the limit of destruction… how do you feel about the risks of using fire as a medium?

Working with fire in making art is very seductive yet risky, because of its unmerciful nature. Fire can represent our greed and egocentric pretensions. Greed has overwhelmed our genuine humble connection with nature, to such an extent that it is now uncontrollable. Working with fire as an artistic medium is not only risky but unpredictable. Sometimes the result has unexpected outcomes. Sometimes it provokes strong feelings, sometimes it destroys everything. Will I ever work with fire again? I don’t know.

I agree with what you say about the importance for artists to “be unbiased in their artistic expression”. But, tell me, is your artistic research more oriented toward an “utopian” integration among different and conflictual agents, or toward a “dystopian” representation of the disaster human beings perpetrate against themselves, above all being so blind toward the environment that enables us to live?

My artistic research is more oriented towards a representation of the disaster human beings perpetrate against themselves and nature. Therefore I consider myself more “dystopian”, as are the most sensitive artists. Nevertheless, I am also trying to be a "ecotopian" citizen, cutting down the consumerist behavior which badly affects the environment. Sometimes I talk about the environmental degradation with visitors who drop by at my studio. Unfortunately, most of them seem unaware and unbothered about the climate change, or sustainability’s development. There are artists who have turned to those issues to take a stand. Others artists engage with these topics because they are the current challenges for our humanity. Scientists, artists, government, cultural agencies, they are trying to make some effective change. But we all know that the impact of these initiatives is slow and that the awareness of climate change and sustainability is a matter of continuous practice, and of a different style of living.

What is your relation with the English language?

The English language was first introduced in Nagaland in the early 1830’s, by American missionaries and the British army. There are officially 16 tribes in Nagaland, and each tribe has its distinct language. There are sub-languages as well, comprising approximately 200 languages. But the education system is in English.

Western media has affected us in tremendous ways, both positive and negative. Our culture has become diluted because of the importance acquired by foreign cultures, which are never ours.

Yes, such a richness risks to get lost, leaving behind the complexities of cultures it neglects… That is why EAS believes that art can be a “language" beyond languages, a more inclusive way for interactions and relationships. Art can rescue what seems to be lost. What is your perspective on this issue?

There is strong evidence that participation in the arts can contribute to community cohesion, reducing social exclusion and isolation, can make communities feel safer and stronger, and most importantly can rescue forgotten cultures for a more inclusive and complex kind of culture. I think that the challenge is to get artists and cultural practitioners to use bigger cross-disciplinary platforms to make their voice heard through the language of art, through media, workshops, seminars, exhibitions and the Internet. I really appreciate Emergent Art Space for the initiatives and support it provides to young artists to realize their efforts in the creation of a more inclusive and larger vision.

Maybe this interview is eventually motivating me to subconsciously reconsider the value of my culture. I think that although the change of society through art is subtle, we cannot understate its outcome.

While working, do you tend to follow an idea or an emotion?

I follow both an idea and an emotion: sometimes ideas direct me first, and then they are followed by emotions, and vice-versa. My practice is inspired by both by Western and Eastern philosophies. However, I believe that the process and the final delivery of the work of art is more interesting and more important than the outcome.

What do you hope to find at the end of a project?

I am trying my best to create each work through processes and using material that might justify my concept. Unfortunately, but maybe fortunately, I am never fully satisfied with every piece I complete, so I kind of rip it off and try to enhance the same particular piece all over again, as in the work of Edvard Munch. He painted “The Scream” almost 20 times in different media and materials since he was not satisfied with it, visually and emotionally. I have no idea how long it will take to complete a project, sometimes I think my art will never be completed unless and until the health of our planet is out of danger. My mentor, the artist and teacher Samindranath Majumdar, always advised us not to expect anything, and just continue to create good art. If it happens, then it happens. If not, then enjoy yourself creating art and bringing solace to yourself.

Since we all hear the scream from the mute Munch’s painting… we hope that your art will be heard as a desperate scream coming from our planet, asking for more attention and love. Thank you Throngkiuba Yim, it was a pleasure to collaborate with you in this interview.