‘Rethinking Museum, Redefining Value: Projecto Ecomuseu’ | Campos de São José, Brasil

What is an Ecomuseum?

Vivien Ahrens, cultural anthropologist and educator from Munich, Germany, explored this question during her Master’s program research in Museology and Social Sciences at the Universidade de São Paulo in 2015/16. “I am fascinated by current debates and projects within New Museology, a movement seeking to broaden the discourse and practice of museums, emphasizing their potential for social change.” Vivien shares here some of her experiences with the Ecomuseum of Campos de Sāo José.

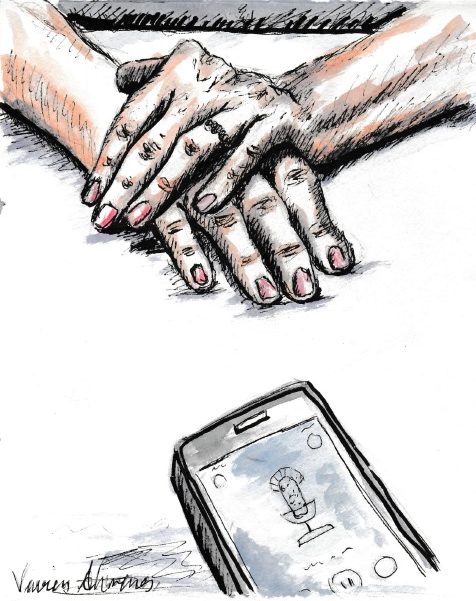

My eyes follow a beam of morning sun light falling through laced curtains onto the living room table. Here, a cell phone lies, ready to record the conversation of us eight: four women, a man, two boys and me. A small digital camera faces Nilcéia, the eldest of the women. She sits upright, her hands folded, resting on the table top. Intently, she looks into the faces of the others. Renata, the youngest of the women begins to speak:

Have you heard of the city park? In that park there is a museum, the Museum of Folklore. The objects in the museum are valuable, right? (…) Now, the idea of the Ecomuseum is as if the whole area, the whole Campos de São José were a museum and everything inside it is important, like these objects. Just that they don‘t have to be objects any more. It can be people, their memories and stories, the school, the Park Alambarí, the creek, the square… everything that people consider their heritage. The goal is to value the heritage of the neighborhood. And I mean handcrafts, cooking, the cake you learned from your grandma, farming. What‘s important for the person in their life, you see? And from there we can make things happen in the neighborhood, starting from what is valuable.

Hesitantly at first, Nilcéia tells her story. She describes how, when she was only 16 years old, she and her husband moved from the Northeastern state of Piauí to Campos de São José. How they constructed their house on the end of the road, when there were still no neighbors, no paved streets, no water system, no bus lines. As we listen, Nilcéia seems to rediscover her own memories, correcting herself, giggling at the details that emerge. As the people and places of her tale grow more recent, her listeners join in, adding anecdotes and jokes. Nadir, Nilceai’s neighbor, will later carefully transcribe the interview, entering places and memories to a register of residents’ statements – the archives of the Ecomuseu Campos de São José.

Inventory? Archive? For whom, by whom? Why speak of museum, heritage and value in Nilceia’s living room?

The Projeto Ecomuseum Campos de São José is based on a broadened understanding of museum. An entire neighborhood and “everything that is seen as valuable“ is considered heritage, and forms the museum’s archive. The project’s goal is “to foster civic engagement through valuing local skills and knowledge“ - a value not defined by a stereotypical museum’s monumental building, exhibition cases or ancient objects, but created through participatory activities.

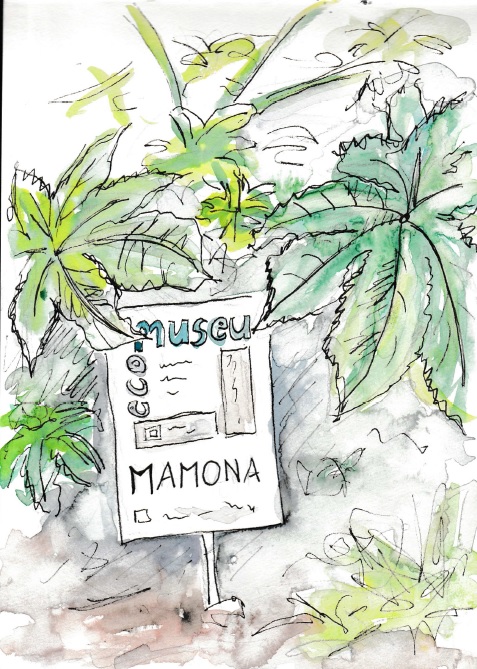

In 2015, Angela Savastano, the director of the Museu do Folclore, decided to take this idea out from the city center into the neighborhood of Campos de São José. An hour by bus from the Museu do Folclore, the neighborhood lies remote of the center’s infrastructure and cultural institutions. The district has been populated since the early 1990s, chiefly by immigrants from the Northeast, who like Nilceia’s family, came in search of better economic opportunities.

Today the residents, largely factory and domestic employees, commute between their workplaces in the center and their homes in “Campos”, spending a good part of their day in full public buses. Many of the youths growing up in the neighborhood, complain that “there is nothing here”. Still, they identify with “Campos”, and resist against the district being called a “favela” by center dwellers, or being discriminated against because of their Northeastern descent. The seniors wish for more contact and interaction with neighbors, who “often don’t even know the name of the family next door”.

Dona Angela, already in contact with residents through other projects, set off on her mission of creating an Ecomuseum. She secured funding and started a small project team of three – director Maria Siqueria, co-worker Renata Sparapan and intern Carol Farnesi. Speaking to neighbors about the idea of the Ecomuseum, they started up regular meetings and activities.

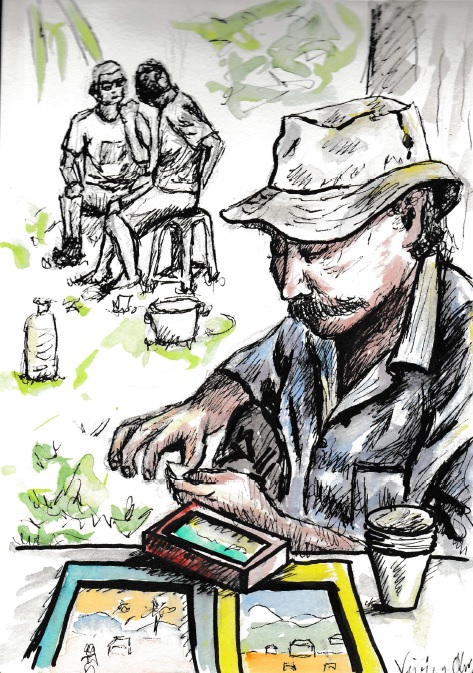

Today, the Ecomuseum unites a group of about 25 residents, mostly senior citizens and school students. During weekly meetings, the “Rodas de Conversa”, every week in a different neighbor’s home, they develop, discuss and coordinate the project’s activities. Next to the “Inventário Participativo” described above, the Projeto Ecomuseu Campos de São José organizes the “Feira dos Saberes e Fazeres”, a fair in the neighborhood park, where arts, crafts, music, food and other skills and knowledge are exhibited. The participants tend to a community garden, a space between the houses, where patches of passion fruit, cauliflower, okra, daisies, tomatoes, zucchini, sweet potatoes and bananas grow, identified by signs with the Ecomuseum’s logo. They organize workshops about a variety of topics, from Northeastern stew recipes, crochet, to building musical instruments from recycled materials. All these activities are portrayed by the participants in the monthly “Campos em Papel”, a neighborhood newspaper, and the project’s online blog http://ecomuseusjc.blogspot.com/

What a museum’s task and relevance are, has become a strongly disputed question. Museums are being thought beyond their traditional core functions of collecting, conserving, researching and interpreting, as a “social factor” and a platform for participation, political activism, or resource for community development.

In Brazil, these discussions gain a specific relevance, as they are being assumed by so-called peripheral neighborhoods, inventing their own museums, for example the 'Museu da Mare' or 'Museu da Favela', in Rio de Janeiro. Here, the concepts of museum and heritage offer a platform for the display of local histories and self-definitions against the background of social inequality and stigma. Also, through self-branding as alternative tourist destinations, wider public attention and new sources of revenue can be gained.

In the Ecomuseu Campos de São José on the other hand, it was not public attention that primarily motivated the members. During the period of my stay, the participants described their experiences with the project very differently. Many of the seniors saw the Ecomuseum as an opportunity to "get out of the house“ and "finally get to know the neighbors“. Others described a more general positive sensation, "I like it, because it makes me feel good. I like how people treat me here“.

Many participants described a changed perceptions of the neighbourhood, "I always thought there was nothing here. Now I know there is a lot“. Or more specifically, "I began to see things differently. For example, how a person can do something interesting, "Those kind of things you always pass on the street, that you didn‘t notice before”. Many described a "rediscovering“ of the neighborhood, and of themselves and their talents, "I didn‘t know what I could do. I thought I didn’t know anything“.

How do the qualities of a museum interact with these experiences? An inventory includes a process of selection and re-contextualization, and thus can be seen as a way to see, organize and give meaning to our surroundings. Certain elements are selected, reorganized, institutionally legitimized and socially recognized through display. Through this process of “musealization”, thus, symbolic value is created. As a process of recontextualization and re-definition, a museum offers a special frame of perception, which does not necessarily require a building, but can function through a specific framing of any every day context.

As “a special frame of perception”, created and manifested within interactions, a museum offers a way of representing the importance of action to oneself and others. It becomes an imaginary monument, a non-material frame, through which value and meaning can be reconstructed and redefined. By becoming part of a museum, neighbors such as Nilceia, have the chance to retell and give new meaning to their own life stories.

To learn more about the Projeto Ecomuseu Campos de São José visit http://ecomuseusjc.blogspot.com/

To read about Vivien Ahrens' thesis bibliography and sources, click here.