‘Return to the Figure’ | San Francisco, California

Emergent Art Space contributor Uji Venkat walks us through her experience at the opening of the XL Catlin Awards Exhibition, in the new space of the San Francisco Art Institute, sharing her thoughts as well as her interview with Kennedy Morgan, one of the artists in the show.

Opening night at the San Francisco Art Institute’s XL Catlin exhibition brought a diverse audience to a warehouse at Fort Mason, showcasing figurative works by forty artists from four countries and nineteen states. With a backdrop of San Francisco lights reflecting in the bay against the dark sky, the illuminated white interiors of the warehouse provided a striking contrast.

This is the first year that the XL Catlin Awards exhibition has come to the United States, following a ten-year running scholarship award in London. The award highlights up-and- coming, innovative young artists.

The audience was as vast and different as the pieces. An amalgamation of races and ages colored the walls and the halls. We saw students, their families, curators, art enthusiasts, and even the occasional techie, given that the San Francisco Bay Area is a rapidly growing hub for the technology industry.

All art exhibitions bring together people of different backgrounds but an interesting aspect of an art show pulling from art colleges and universities around the countries and abroad, is that a public event draws out people of various social milieus and fields. Students are connected to families, peers, academics, and an esteemed panel of judges (1). The show presented this talented group of young artists with a chance for professional exposure. Works selected and on view represented a variety of ethnic and socioeconomic perspectives. Media included oil, acrylic, charcoal, graphite, beaded, and glass works. As exhibiting artist, Kennedy Morgan told me, “We’re in a new age where diversity should be spread.”

When I arrived, I received a minimalist styled, beautifully printed and bound, color catalogue that was free for attendees. It contained an image of each piece presented in the exhibition alongside a snapshot of the artist with statements about their muses and approaches. This in conjunction with the show’s free admission created a sphere of accessibility beyond the reach of traditional gallery shows or museums.

I walked into a salon-style presentation of forty pieces. They were chosen out of a pool of over seven hundred submissions and displayed in this collection (2). Artists, such as XL Catlin finalist Esther Candari, capitalized on the reach of depictions centered in humanity. When asked about her focus in figurative art, she said, “The tangible emotion that you can capture in a depiction of a human figure is a form of communication that is not bound to any specific language or culture and is therefore an extremely powerful tool.”(3)

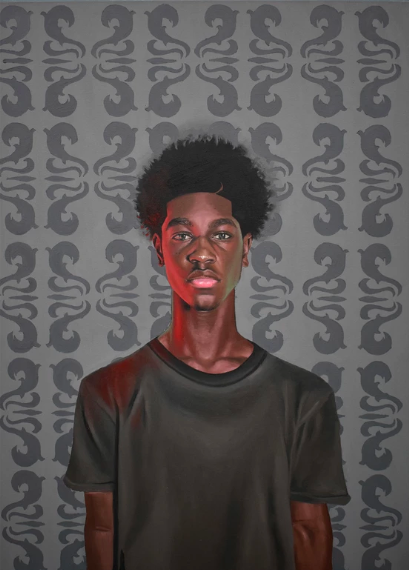

Many pieces were founded in powerful stories. Among them was Jaden. The piece is one in a series of five, depicting a young African American man with a sullen expression and a captivating, direct gaze. His sealed lips have a voice and his body has a presence. There is a red light cast upon the left side of his face and neck, signifying the “danger” current cases, law enforcement, and the political climate have portrayed.

Artist Monica Ikegwu of the Maryland Institute College of Art sheds light on what we are told, what we perceive, and the assumptions we make as a result. Her work, as I have often found in visual arts in contrast to other art forms, illuminates issues without imposing an opinion on the viewer. It merely incites a reconsideration of preconceived notions, to find evidence for judgements. Ikegwu says in her artist statement, “Entering this competition would allow me to share my work with a broad spectrum of people who have never been exposed to my work before.”(4) With the United States being a nation of immigrants, this piece calls attention to the appalling and still ubiquitous racial profiling.

I was awestruck by the empathy and mission these young voices shared. Many of them portrayed influential figures or loved ones in their lives. They emulated the ways they would interact with the world, and portrayed the biases, prejudices, and challenges they face while celebrating the accomplishments and powers they have worked for.

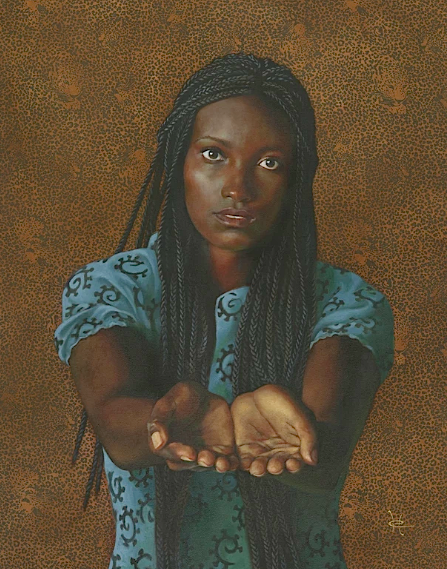

MFA student and show finalist, Esther Candari frequently paints these strong characters. Her submission All I Ask is a portrait of a child trafficking rescuee in Ghana, who has now become a human rights advocate and founder of an NGO freeing other children in Ghana from human trafficking. Founder Lillian Bradley is depicted with her arms patiently outstretched and fiercely juxtaposed by a backdrop of printed leopards. Strength, faith, and understanding are simultaneously conveyed in her fixed expression and stature. A key concentration of Candari’s work is to “succinctly communicate these experiences to a viewer who is unfamiliar with them.”(5)

Drawing attention to this still widespread atrocity and Bradley’s cause is the added contribution of Candari’s piece. As a part of this award show, this piece will travel to three of the priciest US cities, where the vast majority of viewers have not had remotely similar trials or emotions.

These artists, as early as their late teens, are broadening their focus beyond self reflection so their work can connect to a wider audience. Breaking molds through conversation and media, the finalists of the 2018 XL Catlin Award were very conscious about creating approachable pieces.

To delve deeper into what makes and drives one of these impassioned voices, competition finalist Kennedy Morgan shared her insights. She is currently a sophomore student at the San Francisco Art Institute, with a focus in oil painting and a minor in intaglio printmaking. (6)

Earlier in her art career, Morgan adhered to hyper realism with the aspiration that “people would connect to something in the art.”(7) As she expanded her work, she started to focus on detail. Detail can be a connection to the audience, but a greater abstraction moves beyond “this looks good” and helps the viewer ruminate on the subject and message. Comfortable with media such as intaglio, acrylic, and charcoal, Kennedy has started to work more with sculpture, playing with dimensions. She surprised herself with her growing love for contemporary art.

Kennedy traces her passion back to her mother’s support and her “art teacher in elementary school, Mrs. Saute, who saw potential in [her] work and submitted it to some contests.” In middle school, Kennedy started pursuing her own art career. “I started making work for me and not for the class. And developing skills because I liked making art. I was able to start putting concept in my work and I don’t know if I have the ‘right concept’ now but I can stand by it.”

Her eighth-grade art class, close friends, and open access studios inspired her to curate a show in high school. Centrally located in Santa Monica (10) with no admission fee, her audience consisted mostly of people walking by. Curating encouraged her to consider her audience even more. While she had participated in many shows with friends in high school, curating was a very different experience.

Kennedy explains that despite her evolving interests, she has chosen to be a painting major: “I have ideas for large scale paintings. The new space of the San Francisco Art Institute at Fort Mason gives us the chance to actually do that. They give us the wall space, the studio space, the workshop to build stretcher bars. That is where I want to be--to actually make work and large-scale work. The studio allows us to do that, which is so cool."

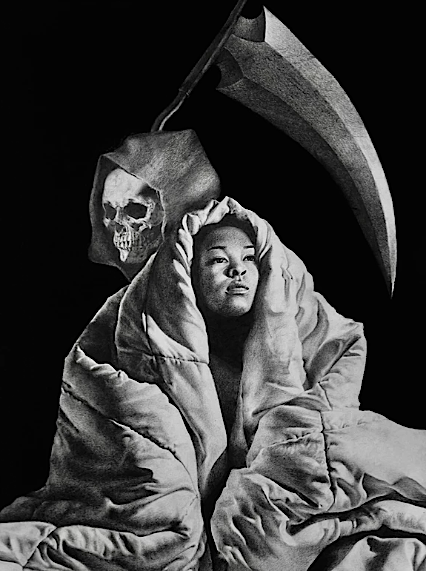

Morgan had started exploring fabric textures in 2015, when she was working on what eventually became her submission for the XL Catlin show. She plays with the eye-catching contrast of black and white and a figure of death. “Everything has an end. Beauty doesn’t last forever. There is a sense of my being under control of a source that I can’t even see. It’s inevitable that I’m going to die...That’s a force that I’m not in control of. But there is also a strong theme of light on me. And I’m looking into it and the future. I see that I have control of what I can do with this life and so, I am also in control.” While her pieces are founded in her present, she “want[s] everybody to see themselves in this painting.” Considering the obstacles, will and perseverance breed opportunity as these forty brave young artists and their inspirations continue to prove.

As a participant in many art scenes, Kennedy’s advice to “all young artists, or anyone who is passionate is to make connections with people, never be nervous to stand by your work, really listen to what people have to say, whether it’s good or bad commentary, because anything will help you. Empathize, make those connections, and you will grow.”

While art can become a very introspective practice, the nature of an art community, built through a school, awards or otherwise, is that of collaboration. Emergent Art Space, like other art communities, thrives because of the visibility and discussion it creates. Exhibitions, articles, forums, blogs, and conversations are only the tip of the iceberg for the creativity that such a community fosters.